Note: This is a slightly edited version of a talk I gave yesterday at Broome Community College in Binghamton, New York. It’s a simple list of 10 things I wish I’d heard when I was in college.

Note: This is a slightly edited version of a talk I gave yesterday at Broome Community College in Binghamton, New York. It’s a simple list of 10 things I wish I’d heard when I was in college.

All advice is autobiographical.

All advice is autobiographical.

It’s one of my theories that when people give you advice, they’re really just talking to themselves in the past. This list is me talking to a previous version of myself.

Your mileage may vary.

1. Steal like an artist.

Every artist gets asked the question, “Where do you get your ideas?”

The honest artist answers, “I steal them.”

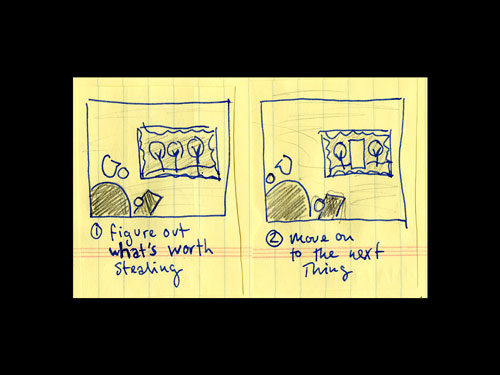

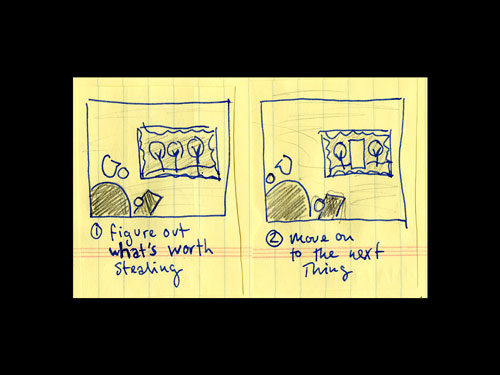

I drew this cartoon a few years ago. There are two panels. Figure out what’s worth stealing. Move on to the next thing.

That’s about all there is to it.

Here’s what artists understand. It’s the a three-word sentence that fills me with hope every time I read it:

It says it right there in the Bible. Ecclesiastes:

That which has been is what will be, That which is done is what will be done, And there is nothing new under the sun.

Every new idea is just a mashup or a remix of previous ideas.

Here’s a trick they teach you in art school. Draw two parallel lines on a piece of paper:

How many lines are there? There’s the first line, the second line, but then there’s a line of negative space that runs between them. See it?

1 + 1 = 3.

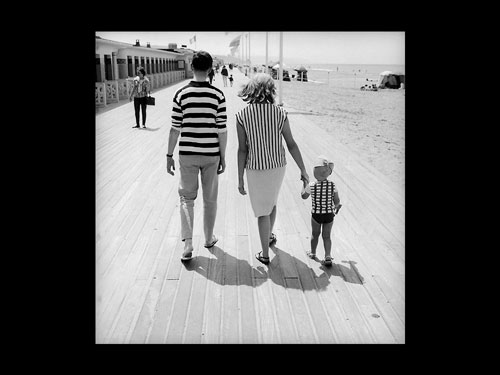

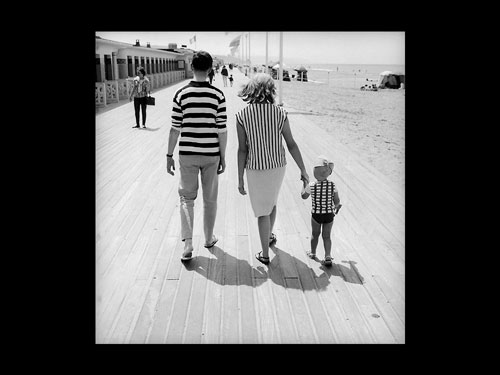

Speaking of lines, here’s a good example of what I’m talking about: genetics. You have a mother and you have a father. You possess features from both of them, but the sum of you is bigger than their parts. You’re a remix of your mom and dad and all of your ancestors.

You don’t get to pick your family, but you can pick your teachers and you can pick your friends and you can pick the music you listen to and you can pick the books you read and you can pick the movies you see.

Jay-Z talks about this in his book,

Decoded:

We were kids without fathers…so we found our fathers on wax and on the streets and in history, and in a way, that was a gift. We got to pick and choose the ancestors who would inspire the world we were going to make for ourselves…Our fathers were gone, usually because they just bounced, but we took their old records and used them to build something fresh.

You are, in fact, a mashup of what you choose to let into your life. You are the sum of your influences. The German writer Goethe said, “We are shaped and fashioned by what we love.”

An artist is a collector. Not a hoarder, mind you, there’s a difference: hoarders collect indiscriminately, the artist collects selectively. They only collect things that they really love.

There’s an economic theory out there that if you take the incomes of your five closest friends and average them, the resulting number will be pretty close to your own income.

I think the same thing is true of our

idea incomes. You’re only going to be as good as the stuff you surround yourself with.

My mom used to say to me, “Garbage in, garbage out.”

It used to drive me nuts. But now I know what she means.

Your job is to collect ideas. The best way to collect ideas is to read. Read, read, read, read, read. Read the newspaper. Read the weather. Read the signs on the road. Read the faces of strangers. The more you read, the more you can choose to be influenced by.

Identify one writer you really love. Find everything they’ve ever written. Then find out what they read. And read all of that. Climb up your own family tree of writers.

Steal things and save them for later. Carry around a sketchpad. Write in your books. Tear things out of magazines and collage them in your scrapbook.

Steal like an artist.

2. Don’t wait until you know who you are to start making things.

There was

a video going around the internet last year of Rainn Wilson, the guy who plays Dwight on The Office. He was talking about creative block, and he said this thing that drove me nuts, because I feel like it’s a license for so many people to put off making things: “If you don’t know who you are or what you’re about or what you believe in it’s really pretty impossible to be creative.”

If I waited to know “who I was” or “what I was about” before I started “being creative”, well, I’d still be sitting around trying to figure myself out instead of making things. In my experience, it’s in the act of making things that we figure out who we are.

You’re ready. Start making stuff.

You might be scared. That’s natural.

There’s this very real thing that runs rampant in educated people. It’s called

imposter syndrome. The clinical definition is a “psychological phenomenon in which people are unable to internalize their accomplishments.” It means that you feel like a phony, like you’re just winging it, that you really don’t have any idea what you’re doing.

Guess what?

None of us do. I had no idea what I was doing when I started blacking out newspaper columns. All I knew was that it felt good. It didn’t feel like work. It felt like play.

Ask any real artist, and they’ll tell you the truth: they don’t know where the good stuff comes from. They just show up to do their thing. Every day.

Have you ever heard of

dramaturgy? It’s a fancy sociological term for something this guy in England

said about 400 years ago:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts…

Another way to say this:

I love this phrase. There’s two ways to read it: Fake it ‘til you make it, as in, fake it until you’re successful, until everybody sees you the way you want, etc. Or, fake it til’ you make it, as in, pretend to be making something until you actually make something. I love that idea.

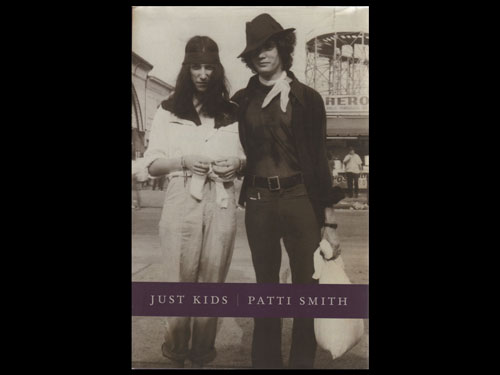

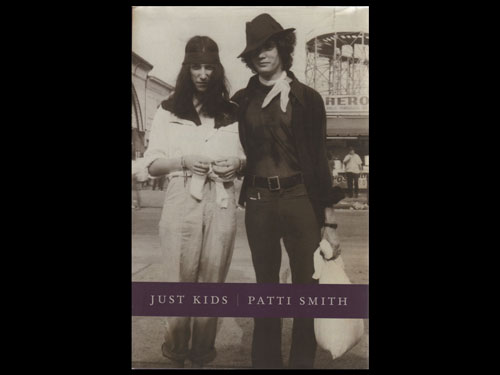

I also love the book

Just Kids by Patti Smith. I love it because it’s a story about how two friends moved to New York and learned to be artists. You know how they learned to be artists? They pretended to be artists. I’ll spoil the book for you and describe my favorite scene, the turning scene in the book: Patti Smith and her friend Robert Maplethorpe dress up in all their gypsy gear and they go to Washington Square, where everybody’s hanging out, and this old couple kind of gawks at them, and the woman says to her husband, “Oh, take their picture. I think they’re artists.” “Oh, go on,” he shrugged. “They’re just kids.”

The point is: all the world’s a stage. You need a stage and you need a costume and you need a script. The stage is your workspace. It can be a studio, a desk, or a sketchbook. The costume is your outfit, your painting pants, or your writing slippers, or your funny hat that gives you ideas. The script is just plain old time. An hour here, or an hour there. A script for a play is just time measured out for things to happen.

Fake it ’til you make it.

3. Write the book you want to read.

Quick story:

Jurassic Park came out on my 10th birthday. I loved it. I was kind of obsessed with it. I mean, what 10-year-old wasn’t obsessed with that movie? The minute I left my little small-town theater, I was dying for a sequel.

I sat down the next day at our old green-screen PC and typed out a sequel. In my treatment, the son of the game warden eaten by velociraptors goes back to the island with the granddaughter of the guy who built the park. See, one wants to destroy the rest of the park, the other wants to save it. Of course, they fall in love and adventures ensue.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I was writing what we now call

fan fiction—fictional stories based on characters that already exist.

10-year-old me saved the story to the hard drive.

Then, a few years later, Jurassic Park 2 came out.

And it sucked.

The sequel *always* sucks compared to the sequel in our heads.

The question every young writer asks is: “What should I write?”

And the cliched answer is, “Write what you know.”

This advice always leads to terrible stories in which nothing interesting happens.

The best advice is not to write what you know, it’s write what you *like*.

Write the kind of story you like best.

We make art because we like art.

All fiction, in fact, is fan fiction.

The best way to find the work you should be doing is to think about the work you want to see done that isn’t being done, and then go do it.

Draw the art you want to see, make the music you want to hear, write the books you want to read.

4. Use your hands.

My favorite cartoonist,

Lynda Barry, she has this saying: “In the digital age, don’t forget to use your digits! Your hands are the original digital devices.”

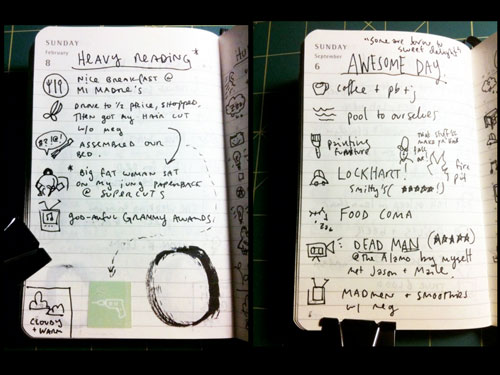

When I was in creative writing workshops in college, all manuscripts had to be in double-spaced, Times New Roman font. And my stuff was just terrible. It wasn’t until I started making writing with my hands that writing became fun and my work started to improve.

The more I stay away from the computer, the better my ideas get. Microsoft Word is my enemy. I use it all the time at work. I try to stay away from it the rest of my life.

I think the more that writing is made into a physical process, the better it is. You can feel the ink on paper. You can spread writing all over your desk and sort through it. You can lay it all out where you can look at it.

People ask me why I don’t develop an iPhone or iPad Newspaper Blackout app, and I tell them because I think there is magic in feeling the newsprint in your hand and the words disappearing under that marker line. A lot of your senses are engaged–even the smell of the fumes add to the experience.

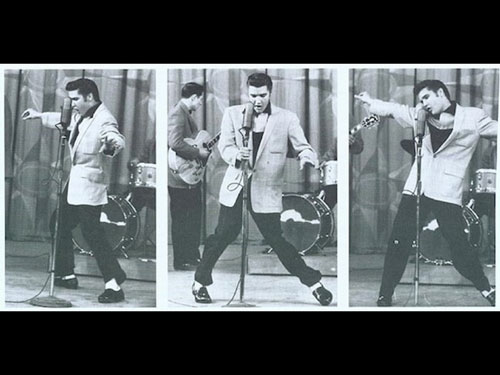

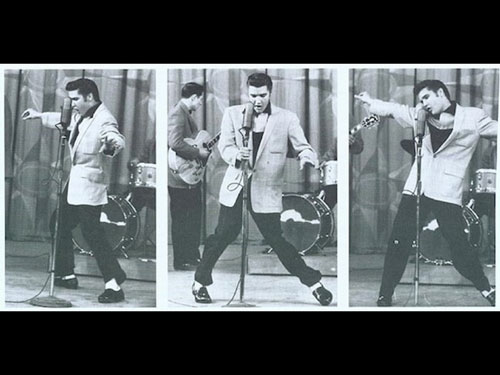

Art that only comes from the head isn’t any good. Watch any good musician and you’ll see what I mean.

When I’m making the poems, it doesn’t feel like work. It feels like play.

So my advice is to find a way to bring your body into your work. Draw on the walls. Stand up when you’re working. Spread things around the table.

Use your hands.

5. Side projects and hobbies are important.

Speaking of play — one thing I’ve learned in my brief tenure as an artist: it’s the side projects that blow up.

By side projects I mean the stuff that you thought was just messing around. Stuff that’s just play. That’s actually the good stuff. That’s when the magic happens.

The blackout poems were a side project. Had I been focused only on my goal of writing short fiction, had I not allowed myself the room to experiment, I’d never be where I am now.

It’s also important to have a hobby. Something that’s just for you. Music is my hobby. (That’s me at Guitar Center.)

While my art is for the world to see, music is for me and my friends. We get together every Sunday and make noise for a couple of hours. It’s wonderful.

So the lesson is: take time to mess around. Have a hobby. It’s good for you, and you never know where it may lead you…

6. The secret: do good work and put it where people can see it.

I get a lot of e-mails from young artists who ask how they can find an audience. “How do I get discovered?”

I sympathize with them. There was a kind of fallout that happened when I left college. The classroom is a wonderful, if artificial place: your professor gets paid to pay attention to your ideas, and your classmates are paying to pay attention to your ideas.

Never in your life will you have such a captive audience.

Soon after, you learn that most of the world doesn’t necessarily care about what you think. It sounds harsh, but it’s true. As Steven Pressfield

said, “It’s not that people are mean or cruel, they’re just busy.”

If there was a secret formula for getting an audience, or gaining a following, I would give it to you. But there’s only one not-so-secret formula that I know: “Do good work and put it where people can see it.”

It’s a two step process.

Step one, “do good work,” is incredibly hard. There are no shortcuts. Make stuff every day. Fail. Get better.

Step two, “put it where people can see it,” was really hard up until about 10 years ago. Now, it’s very simple: “put your stuff on the internet.”

I tell people this, and then they ask me, “What’s the secret of the internet?”

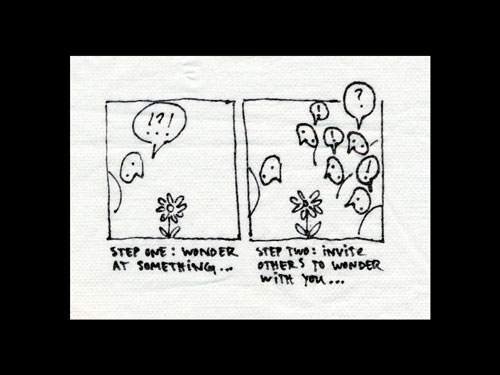

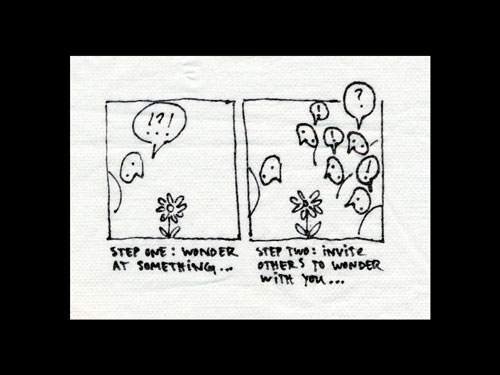

Step 1: Wonder at something. Step 2: Invite others to wonder with you.

You should wonder at the things nobody else is wondering about. If everybody’s wondering about apples, go wonder about oranges.

One of the things I’ve learned as an artist is that the more open you are about sharing your passions, the more people love your art.

Artists aren’t magicians. There’s no penalty for revealing your secrets.

Believe it or not, I get a lot of inspiration from people like Bob Ross and Martha Stewart. Bob Ross taught people how to paint. He gave his secrets away. Martha Stewart teaches you how to make your house and your life awesome. She gives her secrets away.

People love it when you give your secrets away, and sometimes, if you’re smart about it, they’ll reward you by buying the things you’re selling.

When you open up your process and invite people in, you learn. I’ve learned so much from the folks who submit poems to the

Newspaper Blackout site. I find a lot of things to steal, too. It benefits me as much as it does them.

So my advice: learn to code. Figure out how to make a website. Figure out blogging. Figure out Twitter and all that other stuff. Find people on the internet who love the same things as you and connect with them. Share things with them.

7. Geography is no longer our master.

I’m so glad I’m alive right now.

I grew up in the middle of a cornfield in Southern Ohio. When I was a kid, all I wanted to do was hang out with artists. All I wanted to do was get the heck out of southern Ohio and get someplace where something was happening.

Now I live in Austin, Texas. A pretty hip place. Tons of artists and creative types everywhere.

And you know what? I’d say that 90% of my mentors and peers don’t live in Austin, Texas. They live on the internet.

Which is to say, most of my thinking and talking and art-related fellowship is online.

Instead of a geographical art scene, I have

Twitter buddies and Google Reader.

Life is weird.

8. Be nice. The world is a small town.

I’ll keep this short. There’s only one reason I’m here. I’m

here to make friends.

Kurt Vonnegut said it best: “There’s only one rule I know of: goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”

The golden rule is even more golden in our hyper-connected world.

An important lesson to learn: if you talk about someone on the internet, they will find out. Everybody has a Google alert on their name.

The best way to vanquish your enemies on the internet? Ignore them.

The best way to make friends on the internet? Say nice things about them.

9. Be boring. It’s the only way to get work done.

As Flaubert said, “Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.”

I’m a boring guy with a 9-5 job who lives in a quiet neighborhood with his wife and his dog.

That whole romantic image of the bohemian artist doing drugs and running around and sleeping with everyone is played out. It’s for the superhuman and the people who want to die young.

The thing is: art takes a lot of energy to make. You don’t have that energy if you waste it on other stuff.

Some things that have worked for me:

Take care of yourself.

Eat breakfast, do some pushups, get some sleep. Remember what I said earlier about good art coming from the body?

Stay out of debt.

Live on the cheap. Pinch pennies. Freedom from monetary stress means freedom in your art.

Get a day job and keep it.

A day job gives you money, a connection to the world, and a routine.

Parkinson’s law: work expands to fill the time allotted. I work a 9-5 and I get about as as much art done now as I did when I worked part-time.

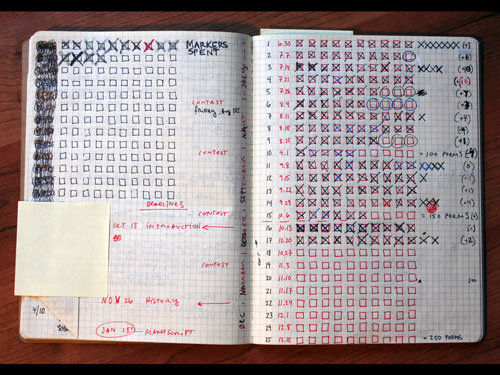

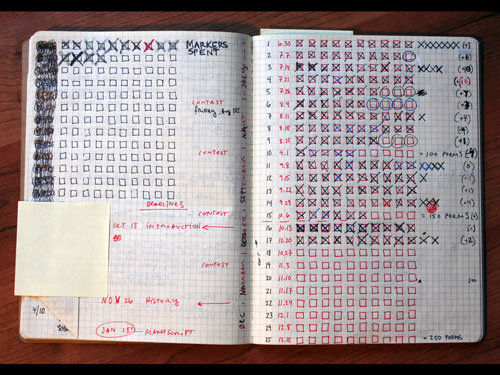

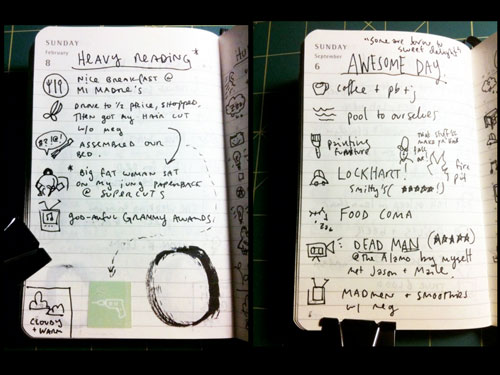

Get yourself a calendar. (And a logbook.)

You need a chart of future events, and you need a chart of past events.

Art is all about the slow accumulation over time. Writing a page one day doesn’t seem like much. Do it for 365 days and you have a big novel.

A calendar helps you plan work.

This is the calendar I used for my book:

A calendar gives you concrete goals, keeps you on track, and the nice reward of crossing things off and watching the boxes fill up.

Any goal you want to accomplish: get yourself a calendar. Break the task down into little bits of time. Make it a game.

For past events, I suggest

a logbook. It’s not a regular journal, it’s just a little book in which you list the things you do every day. You’d be amazed at how helpful having a daily record like this can be, especially over several years.

Marry well.

It’s the most important decision you’ll ever make.

And marry well doesn’t just mean your life partner — it also means who you do business with, who you befriend, who you choose to be around.

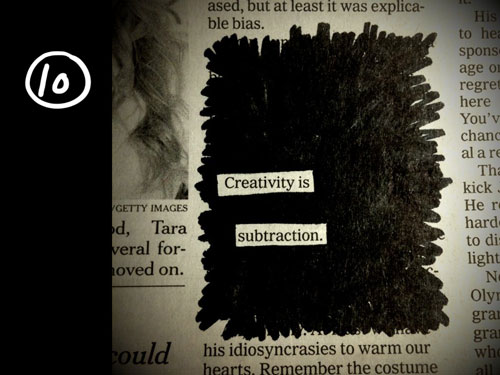

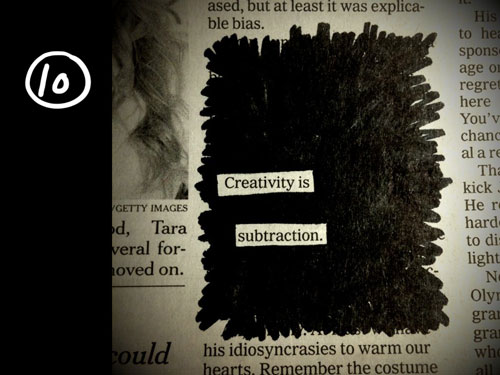

10. Creativity is subtraction.

It’s often what an artist chooses to leave out that makes the art interesting. What isn’t shown vs. what is.

In this age of information overload and abundance, those who get ahead will be the folks who figure out what to leave out, so they can concentrate on what’s important to them.

Devoting yourself to something means shutting out other things.

What makes you interesting isn’t just what you’ve experienced, but also what you haven’t experienced.

The same is true when you make art: you must embrace your limitations and keep moving.

Creativity isn’t just the things we chose to put in, it’s also the things we chose to leave out. Or black out.

And that’s all I think I have.

Thanks, y’all.